Bind, Security, and Input Validation

Excerpt from an internal email at EPS/CODE:

The latest version of CODE Framework has some pretty significant enhancements around binding, security, and input-validation. It is a big set of features that can be used either individually, or in a way that ties them all together. I am not totally sure where to start. One way to look at it is that we have new binding syntax. So when in the past you did this:

<TextBox Text="{Binding Description}"/>

You now instead can do this:

<TextBox Text="{ex:Bind Description}"/>

So what the heck is going on here? Why would I be introducing a different binding syntax? I assume most of you didn’t see this feature coming 😃. But I assure you that it is actually pretty cool and there are reasons for it. (Plus, as always in CODE Framework, this is a completely optional feature and not required…). But let me start at the beginning and provide some background information and some information about related features. Because not just do we have a new way to bind, but we have also worked on new input-validation as well as the security system. Let’s start with the security system:

New CODE Framework WPF UI Security System

CODE Framework has always had features that use the built-in security system in WPF, which is based on having a logged in user that is available on every thread at all times. Users have roles and we leverage that feature. For instance, all our view-actions allow for a security role assignment, so the actions are only available to the users who are in certain roles. We now have more such features and they are specific to the UI. This standardizes what we have been doing on projects individually and makes this part of the core WPF framework.

So here is how it works: On any WPF UI Element, you can now set attached properties to define security. For instance, you can now do this:

<TextBox Text="Secret!"

sec:Security.FullAccessRoles="Super Admin, Super Hero"

sec:Security.ReadOnlyRoles="Normal Admin" />

So this is pretty straightforward. If the current user happens to be in either the “Super Admin” or “Super Hero” roles, the user can edit the textbox. (Note: Users can have any number of assigned roles, but as long as one of the user’s roles is one of the two, full access is granted). Similarly, if the user is in the “Normal Admin” role, read-only access is granted. (Note: If the user is both a “Normal Admin” and a “Super Admin”, then full access is granted). This works on any and all WPF UI Elements. (Note: Some elements, such as textboxes, support a true read-only states, which is used by the security system. For other controls, the system simply disables the control to use the disabled state as a poor-man’s read-only flag).

These security roles are a mechanism to add restrictions. If full-access roles are defined, then only those in the roles are allowed full access. If the setting isn’t present on the other hand, then no restriction is applied and everyone has full access. Similarly, if read-only roles are defined, then only those in the appropriate roles are given read-only access. Everyone else just won’t even see the control. Unless they have full-access of course. If full-access roles is defined but no read-only roles are defined, then everyone who isn’t in full-access is granted read-only access. So it makes sense to only set security for full-access and let everyone else default to read-only. The opposite does not typically make sense, because without restriction on full access, everyone has full access and thus read-only access is never checked.

Note that the “sec” namespace can really be anything you want it to be, but I think “sec” makes sense. It should be defined like this in the root element of the XAML file:

xmlns:sec="clr-namespace:CODE.Framework.Wpf.Security;assembly=CODE.Framework.Wpf"

So this is cool, because it is a very simple, yet super-effective way to define security on UI elements. However, it would sometimes also be nice to define this kind of security right on properties of a view-model. For instance, if our textbox was bound to a “Description” property on the view-model, then it would be nice to define the security on the view-model, rather than on the view. After all, the view-model could be used in different views, and we wouldn’t want to have to re-define the security everywhere independently as that would be verbose and also a likely source of errors. For this reason, we now also have a [Security] attribute that allows us to do this on a property:

[Security(FullAccessRoles = "Super Admins, Super Heroes", ReadOnlyRoles = "Normal Admins")]

public string Description

{

get { return _description; }

set

{

_description = value;

NotifyChanged(nameof(Description));

}

}

So that is pretty neat. Security information now goes directly with the data element we want to secure. The only problem is that this is just some meta-information that doesn’t really do anything. What we need is some way to have the UI automatically pick this up. Hmmm….

AttributeBinding Markup Extension

To solve this problem, I introduced a new sub-system that extends the XAML syntax and allows properties to be bound to various aspects of attributes. For instance, let’s say we have a property like this:

[Something]

public string SomeInformation { get; set; }

So this “SomeInformation” property has a custom attribute called “Something” set. (Yeah… not coming up with good examples here, but just roll with it J). Now let’s say in the UI, we want to bind the IsEnabled property of a textbox to whether that attribute is set/present or not. Using our super-duper markup extension, we can now do this:

<TextBox Text="{Binding SomeInformation}" IsEnabled="{ex:AttributeBinding SomeInformation, Name=Something, Mode=IsAttributeSet}" />

This new attribute binding, binds not just to the “SomeInformation” property (as a normal binding would), but it binds to the attribute named “Something” on that property. And since the Mode is set to “IsAttributeSet”, the return value will be true if the attribute is found. So if someone removed the attribute later, the control would end up being disabled.

There are several different modes for attribute bindings:

- IsAttributeSet: Returns true, if the attribute is in fact applied.

- Attribute: Binds the actual attribute to the target. (This requires that the target is of type Attribute or object).

- Attributes: Binds a list of maching attributes (as IEnumerable

) to the target. - AttributeProperty: Binds the value of a property on an attribute to the target.

Note that the syntax can actually be simplified a bit. For instance, the above example can actually also be written like this:

<TextBox Text="{Binding SomeInformation}" IsEnabled="{ex:AttributeBinding SomeInformation[Something], Mode=IsAttributeSet}" />

There also is an even more specialized markup extension based on this that makes the syntax even more concise:

<TextBox Text="{Binding SomeInformation}" IsEnabled="{ex:AttributeSet SomeInformation[Something]}" />

All of these are functionally equivalent.

Checking for whether an attribute is set is nice, but the most useful kind of attribute binding is to bind to a property on an attribute, and that gets us right back to our security system, because using attribute property binding, we can do this:

<TextBox Text="Secret!"

sec:Security.FullAccessRoles="{ex:AttributePropertyBinding Description[Security.FullAccessRoles]}"

sec:Security.ReadOnlyRoles="{ex:AttributePropertyBinding Description[Security.ReadOnlyRoles]}" />

A-ha! Now we are getting somewhere. This automatically binds the security settings from the attribute we applied to the Description property to our new UI security setup. Yay!

Note: The “ex” namespace for the markup extensions is defined like this:

xmlns:ex="clr-namespace:CODE.Framework.Wpf.MarkupExtensions;assembly=CODE.Framework.Wpf"

So bottom line: We now have new security features that do not just set security on the UI, but we can define security right on the view-model declaratively (“through attributes”) and then bind those attributes to the UI features.

New CODE Framework Input Validation System

Another area I have been working on is UI Input Validation. As you probably are aware, WPF does have a way to validate input by assigning validation to the binding system. So that has always been there, and will be at our disposal in the future. However, as some of you may know, I have never been all that fond of that system, due to its limitations and characteristics. For one, this type of input validation is always tied to a binding. I guess in a sense, that is not that much of a limitation for us, since we always bind all our UI elements to view-model properties. However, what makes it nasty is that the syntax for this is a royal PITA and turns what would otherwise be very simple and clean XAML into a complete mess. Plus, the system is really not extensible in ways I want it to be. Therefore, I decided to create a standardized approach for CODE Framework.

This system will grow over time. Initially, it is NOT based on WPF ValidationRule class (which you can already use through standard WPF bindings anyway), but instead it is based on data annotations, just like ASP.NET MVC. (We will add other features in the future… this system can really grow quite a bit). The basic idea is that we can define a property on the view-model in the following fashion:

[Required(ErrorMessage = "The Description field is required and can't be left blank.")]

[MinLength(10, ErrorMessage = "Please provide at least 10 characters for a description.")]

[MaxLength(50, ErrorMessage = "Please provide no more than 50 characters for a description.")]

public string Description

{

get { return _description; }

set

{

_description = value;

NotifyChanged(nameof(Description));

}

}

There are of course numerous different such annotation attributes pre-defined in the standard System.ComponentModel.DataAnnotations namespace in .NET. And you can always create your own if need be. So that is nifty, because we now have a way to declaratively create validation rules and also extend that system as needed. Plus, it is the same system that is already known to ASP.NET MVC developers.

Once again, we have the same issue as with security. How do we get the UI elements to know about these rules and make them enforce them? Well, as you probably guessed, there is an attached property you can set on any element you want. And since we have our fancy attribute binding extension, we can bind that attached UI property to the attributes on the Description property like so:

<TextBox Text="{Binding Description}" val:InputValidation.ValidationAttributes="{ex:AttributeBinding Description[Validation], Mode=Attributes}"/>

This may be a bit confusing, but basically we have a ValidationAttributes property that, when set, looks at all the attributes and then performs appropriate validation on the UI element. We are binding this to all “Validation” attributes on the Description property using Attributes Mode. (Note: All validation attributes inherit from an attribute called “Validation” and therefore are included in this attribute binding). So this is a bit confusing in syntax. I therefore created a shortcut:

<TextBox Text="{Binding Description}" val:InputValidation.ValidationAttributes="{ex:AttributeValidationBinding Description}"/>

This automatically knows how to pick up all validation attributes on the Description property. Yay again!

Note: Here is the definition of the “val” XAML namespace:

xmlns:val="clr-namespace:CODE.Framework.Wpf.Validation;assembly=CODE.Framework.Wpf"

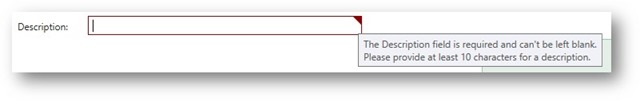

Of course it doesn’t do as much good to know that validation failed. We also need to show that in the UI somehow. This relies on the controls in our themes to recognize validation errors. This is very much a work in progress, and I have only styled the textbox in the Workplace theme to respect this yet (more to come soon… all our controls in all themes will respect this). Here is what such a textbox looks like when there is a validation error:

Of course this may look completely different in different themes, and as everything else in CODE Framework, this style can be completely re-defined in different apps.

Note that this example is a little bit contrived. The MinLength requirement would automatically take care of the Required requirement. But hey! I wanted an example with a few different rules 😃.

There also is a bit of a special case here. Since there is a MaxLength validation attribute that gets applied, this is not just a rule that gets validated, but it also sets the MaxLength property on the textbox, so users can’t even try to type something longer. This is one example for additional logic beyond just brute-force validation. It is possible that we will add similar features in the future. For instance, if we were to apply a PhoneNumber validation rule, or an Email validation rule, we may go out of our way to only allow characters valid for these scenarios. We’ll see. As you can imagine, this is not a small feature set and will have to grow over time.

Note: The validation system will also need other features in the future. We need to be able to check validation not just automatically through the UI, but we need to be able to add code to a view-model where we can easily say “is this model valid?”. We also need other ways to add complex validation that is not based on attributes. I will keep you informed as those are being added.

Note: More information about input validation can be found in the [Input Validation in WPF] topic.

Putting it all together

So this is a pretty cool feature set and a huge update. As a result, we can now define our property like this (including all the attributes we have encountered so far):

[Required(ErrorMessage = "The Description field is required and can't be left blank.")]

[MinLength(10, ErrorMessage = "Please provide at least 10 characters for a description.")]

[MaxLength(50, ErrorMessage = "Please provide no more than 50 characters for a description.")]

[Security(FullAccessRoles = "Super Admin, Super Hero", ReadOnlyRoles = "Normal Admin")]

public string Description

{

get { return _description; }

set

{

_description = value;

NotifyChanged(nameof(Description));

}

}

That is nice and puts everything we need in one place.

Then, we can define our UI element like so:

<TextBox Text="{Binding Description}"

sec:Security.FullAccessRoles="{ex:AttributePropertyBinding Description[Security.FullAccessRoles]}"

sec:Security.ReadOnlyRoles="{ex:AttributePropertyBinding Description[Security.ReadOnlyRoles]}"

val:InputValidation.ValidationAttributes="{ex:AttributeValidationBinding Description}"/>

So that is pretty cool, but man, it is verbose and probably hard to remember. You can certainly do this of course, but there is a simpler way, which brings us full circle:

<TextBox Text="{ex:Bind Description}"/>

This is the exact equivalent of the longer version. The new “Bind” syntax is fully aware of validation as well as security (and possibly other things in the future). It binds to the Description property, just like a standard WPF Binding would (and all Binding features are available, since it uses a standard Binding for that part). In addition, it also inspects the Description property to see if it has validation attributes and whether it has the Security attribute set. If it finds anything useful, it will set up all the appropriate bindings for those as well. (The Bind object even has properties you can set to indicate whether you want to respect security and validation, but both of those are true by default, so you shouldn’t have much need to mess with those).

And there you have it! This is quite the change. It is optional to use, but I think it is very appealing. We can now define a lot of things on our view-model in very simple ways. And using the Bind syntax, we can’t forget to respect any of these things or set the link up wrong. I think that is pretty cool.

Creating Custom Validation Attributes

Validation attributes such as [Required] are standard .NET attributes (data annotation attributes) and not specific to CODE Framework. You can simply create a new attribute class that derrives from ValidationAttribute (or any of the other existing validation attributes, such as RequiredAttribute) and override the IsValid() method.

There is a custom extension in CODE Framework however, which can be used optionally. Attributes such as [Required] are relatively simple. The value is either there, or it isn't. However, in many business applications, scenarios are more complex. For instance, it is easy to imagine a scenario where a value is only required if certain other conditions are true. But for that, the IsValid() method in the attribute has to have access to other properties on the model object. This isn't easily possible. For this reason, CODE Framework introduces the concept of a “context object”. If an attribute implements the IValidationWithContextObject interface, then the parent object (the object that contains the property with the attribute) is set as the ContextObject property of the attribute. This object can then be used in the IsValid() method to make further decisions. (Note: If other objects need to be accessed from within that method, it is recommended that you add a reference to that object within the context object).